Bobby Jenks closed out a World Series – and opened doors to baseball's next generation: "Owe my career to that man"

"I'm not afraid anymore," Jenks told best friend Toby Hall, just days before his death.

A few days before July 4, Bobby Jenks’ thoughts were right where they’d always been — with the family he lived for and the game he loved.

More than anything, Jenks wanted to be in Chicago this weekend, as the White Sox celebrated the 20th anniversary of their 2005 World Series title — a title he helped seal with his rookie-year excellence.

Stage 4 adenocarcinoma, a form of stomach cancer, had taken its toll. There was no way he’d have the strength to fly from Portugal — where he’d been living with his wife and two of his six children to be closer to her family — to the Windy City.

The illness wasn’t the only thing that wore him down. Just months earlier, Jenks and his family lost their California home in the Palisades wildfires — all of his possessions destroyed, except for the World Series ring.

“I’ve got one suitcase left to my name,” Jenks told MLB.com in February from a hospital bed in Sintra. “It’s all gone. Everything else I’ve ever done. I have everything, first to first. All those things are irreplaceable.”

Jenks overcame a lot: a rough childhood, academic struggles, immaturity, preconceived notions, a spate of injuries, being cut by his first MLB organization, a botched back surgery, and addiction.

This felt like the knockout punch — after a lifetime of brushing off right hooks.

“Everything he was going through…everybody thinks we’re all multi-millionaires and nothing’s ever going to be an issue,” said Toby Hall, Jenks’ longtime friend and former batterymate with the White Sox, during a phone interview. “But when this happens…it’s just heartbreaking.”

Still, like he’d done on the mound countless times, Jenks made the pitch to Hall.

“He goes, ‘I can’t make it out, but Eleni and the kids are going there. I’m asking you to stand in with her. I couldn’t ask for a better person to be there with my family to represent me,’” Hall said of Jenks’ request to join his family at Rate Field for the weekend’s festivities.

Hall is no stranger to standing in for Jenks. He took over as interim manager of the independent league Windy City Thunderbolts after Jenks’ diagnosis.

As Jenks underwent treatment, the two spoke often — always circling back to baseball and the group of players they were building together.

That Wednesday was no different.

“It was just a normal conversation,” Hall said.

“We were going over different things, just talking and he goes, ‘I’m not scared anymore.’”

Two days later, at the age of 44, Jenks passed away.

WIN-DY CITY

One of Jenks’ goals was to return as the ThunderBolts’ skipper in 2025. Players and coaches raved about the impact he had in his lone season at the helm in 2024 — and his fingerprints are all over this year’s team.

And Jenks never let Hall forget about the “I” word in front of his job title.

“Yeah, he got a kick out of that,” Hall said with a laugh. “He goes, ‘Just remember — there’s an I on that Interim.’”

That’s part of what made July 5 the hardest day Windy City’s players endured as pros.

As the ThunderBolts wrapped up batting practice ahead of a game against the Brockton Rox, the team’s trainer approached captain Christian Kuzemka.

“He was like, ‘Just tell everyone not to check their phones before the game,’” Kuzemka, 29, recalled during a phone interview.

In the outfield, pitcher Trevin Reynolds, 27, was shagging fly balls when he got the same message.

“The first thing on my mind wasn’t even Bobby, I didn’t want to think like that,” Reynolds said, holding back tears.

As news of Jenks’ passing circulated, Kuzemka knew any attempt to stop it was futile. He made his way to the bullpen to break the news to the pitchers.

An emotional Hall addressed the team with a simple message: “Win the game, and we’ll deal with it afterwards.”

“We went from having a normal day to having a moment of silence for Bobby within 30 minutes,” Kuzemka said.

Trailing 5–3, Windy City rallied for two in the eighth to tie it, then pushed across the go-ahead run in the ninth to seal a 6–5 win.

“Those were Bobby’s favorite wins, the gritty come-from-behind wins,” Kuzemka said. “That part of it, you probably couldn’t have written a better script for that game from our standpoint.”

Of course he loved those kinds of wins — they mirrored just about every part of his baseball career and personal life.

By all accounts, Jenks had the kind of talent that should’ve gone higher than the fifth round of the 2000 MLB Draft — but teams were wary of the 6-foot-3, 230-pound right-hander whose ERA and GPA weren’t far apart.

“Yeah, well,” Jenks told the Orange County Register, asked why he fell to the fifth round despite first-overall pick potential. “It’s a long story.”

Poor grades made him ineligible at Timberlake High every year but his sophomore season — a reflection not of ability, but of disinterest in school and the lack of structure around him.

“His parents were not really in the picture, and while I would not call it abusive, it was, ‘Do what you want to do, Bobby,’” Seattle-based coach Mark Potoshnik told the Chicago Tribune.

Potoshnik didn’t just believe in Jenks — he brought him to Seattle, let him crash at his place, and trained him at the Northwest Baseball Academy to make sure scouts finally saw him.

His only real high school showcase came with the American Legion’s Prairie Cardinals, including a 1999 summer where he went 9–3 with a 2.15 ERA, 127 strikeouts, two no-hitters, and a .400 average with eight homers.

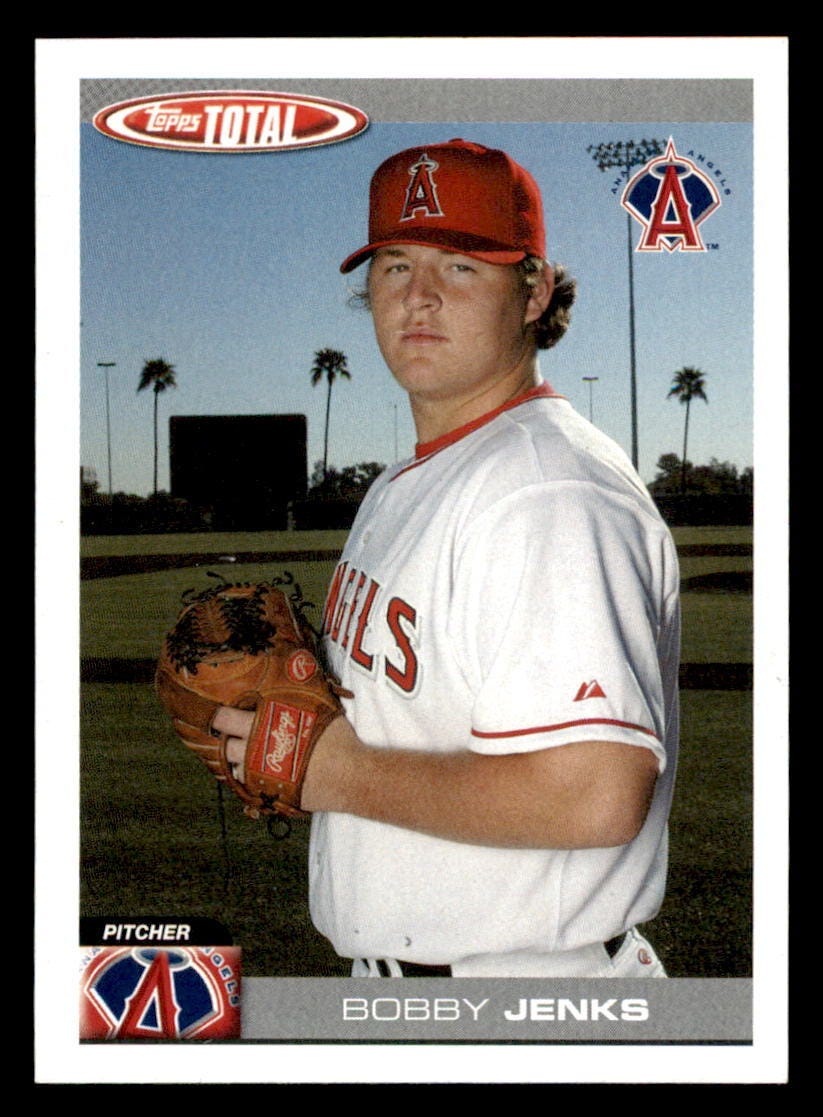

The Angels were enamored by the righty – who’d drawn comparisons to Roger Clemens and Kerry Wood– and his blistering heater, knee-buckling curveball, and ace potential.

“Jenks is not as polished as some of our other kids,” then-Angels skipper Mike Scioscia said. “But there’s no question he’s got the highest ceiling of the bunch.”

By December 2004, injuries and off-field concerns had piled up. Jenks wore out his welcome and was designated for assignment.

“I think if you were to ask him, he would’ve said, ‘Sometimes you just need to get slapped in the face,’” said Mike Butcher, Jenks’ former pitching coach and close friend. “That was a little wake-up call for him.”

“He lived a great life and a very fulfilling life with a lot of love and happiness and just wanted to give back, which is what you do. But when you have all that knowledge and wisdom, it means nothing if you can’t give it away, it means nothing.”

Jenks’ wisdom was hard-earned, shaped by the bumps and bruises of minefields throughout his life and career — some self-inflicted, some dealt by a world that didn’t always cut him a break.

“I think at the end of the day Bobby had a master's [degree] in just being a professional baseball player,” Butcher said.

NO ANGEL

When outfielder Jason Coulie reported for his first season of professional baseball in 2000, he was randomly assigned a roommate – a strong-armed pitcher who had been taken five rounds earlier.

“I just remember the strongest hand and strongest handshake I’d ever felt in my entire life,” Coulie recalled during a phone interview about his first time meeting Jenks.

“He knew it. He’d shake someone’s hand, squeeze, and look at you until you had to wave the white flag.”

Coulie had never heard of Jenks; he didn’t read local Idaho newspapers to know of Jenks’ upside and red flags. He just knew the articulate teammate with whom he ate every breakfast, lunch and dinner.

“He was a storyteller, he loved talking about where he was from,” Coulie said, reminiscing about Jenks’ tales of growing up in Spirit Lake, Idaho, a town of less than 800 people when the family relocated in 1993.

“He was so proud that he came from a small town.”

Chris Bootcheck, a fellow starter in the Angels’ minor league system, remembered Jenks as a “bigger than life” presence who made everyone else take notice.

“Everyone’s gauging how close you are to the big leagues, what they can and can’t do,” Bootcheck said. “And I just think his physical presence, you know, set him apart from a lot of people.”

Butcher met Jenks when he reported to Butte, Montana, shortly after being drafted, and saw two distinct yet powerful sides to Jenks. The guy who kept it loose with teammates before games and the savant of sorts, whose memory and attention to detail were beyond his years.

“There’s certain things that separate players apart from others,” Butcher said. “And one was, at 18 years old, Bobby Jenks could recall every single pitch that he threw in a game, every single pitch. Whether it was a fastball up, a fastball in, a fastball outside, whether it was a curveball, he could go over every hitter and recall every single pitch.”

Jenks also met his first wife, Adele, while in the Angels system and started a family, which he consistently credited with overcoming a pattern of immaturity.

"I've got responsibilities now, and I know which direction I need to head," Jenks told The Standard-Times.

There was also the Jenks profiled in a blistering 2003 ESPN article as a self-mutilator who willingly burned his pitching hand in a drunken stupor, lived near an Aryan Nations compound with a “tormented father and a restless mother,” and scared off nearly every team.

The story depicted him less like a misunderstood pitching prodigy and more as a real-life Calvin “Nuke” LaLoosh from “Bull Durham” — a million-dollar arm with a five-cent head who has been suspended and demoted for bringing beer on a team bus.

Jenks’ ex-agent, Matt Sosnic, who served as one of the story’s main sources, volunteered a generationally cold take.

"Imagine being in the top five in the world at what you do, and your demons are so terrible that your ability is dwarfed," Sosnick said. "That's Bobby Jenks. The worst thing that could happen is if he gets to the big leagues. If he gets to the big leagues, he'll free-fall. He can't handle success."

The mix of conduct concerns and arm troubles dampened the Angels’ view of Jenks, leading to his DFA.

“Bobby had some things he needed to overcome as a young man, just like a lot of guys do,” Butcher said. “...I mean, yeah, he got in a little bit of trouble, and what I like about Bobby is he acknowledged it, and he did something about it and got better, and became the man he was.

“There's guys that continue to do the same thing over and over again, and then those guys that do things, then they realize they can't do it anymore, and they make a change, and Bobby made a change, and it was for the better.”

The White Sox acquired Jenks, and it proved to be some of the best $20,000 spent on a waiver claim in history.

"I don't know how the Angels just let him go,” then-White Sox slugger and now Hall of Famer Frank Thomas said.

Despite certain things written in the wake of his passing, Jenks was much more than a player on the roster – and you have to look no further than his “crushed” teammates.

“It’s awful,” Jenks’ former catch A.J. Pierzynski said on Chicago Sports Network. “There’s really no words to describe how sad and how destroyed you are when you think of Bobby being gone.”

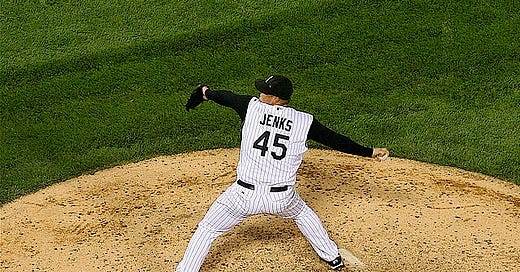

He came up from Double-A midseason, hit 102 mph on his first pitch and recorded the final out of the 2005 World Series in Houston, hoisting Pierzynski in the air to celebrate – an image that has become iconic in Chicago sports history.

The next two seasons, he was an American League All-Star. In 2007, he tied an MLB record by retiring 41 consecutive batters. He has the second-most saves in White Sox history with 172, behind Bobby Thigpen’s 201.

“The Angels may have felt like he wasn't going in the direction where he may be productive, so they pulled the plug,” Jenks’ longtime agent Kenny Felder said. “Most guys who were designated for assignment before getting to the big leagues never really have a career, and this guy was an outlier.

“Probably one of the top two athletes I've ever worked with.”

‘BETTER NOT SUCK’

Nearly two decades earlier, the Wheaton, Illinois, native Kuzemka watched Jenks close out the 2005 World Series on television with his dad, Mark.

Last season, on the anniversary of his father's passing – also from stomach cancer – Kuzemka found himself being consoled by Jenks after a Thunderbolts game.

“The big thing that stands out is just how much he cared about us,” Kuzemka said.

It was a full circle moment for Kuzemka when Jenks came onto the team bus in St. Louis last season, and had a surprise for him as “the only real White Sox fan here.”

“Try this on,” Jenks said, handing Kuzemka his 2005 World Series ring.

Later that same season, as the team weighed moving Kuzemka to the outfield, Jenks gifted him his old glove that he used to shag flyballs.

On account of Jenks’ home burning down, Kuzemka is determined to get the glove back to his family.

“Since he lost everything, his ring and that glove are pretty much all he has for his career,” he said.

Trevin Reynolds first crossed paths with Jenks in 2021, when they were both with the Pioneer League’s Grand Junction Rockies. Jenks was the pitching coach; Reynolds, the pitcher.

A year later, when Reynolds’ then-girlfriend lost her mother to cancer, he took Jenks up on his open-door policy.

“First thing I did was go to Bobby and kind of broke down to him and stuff, because that's what he told us to do,” Reynolds recalled.

Last season, Reynolds — newly engaged and rehabbing from arm surgery — served as Windy City’s assistant pitching coach. He still spent plenty of time with Jenks, often driving his manager to and from the ballpark.

Even then, Jenks had wisdom to share.

“He would get onto me about calling my fiancée after the games,” Reynolds said. “I would drive him to the games and he's like, ‘Did you call your fiancée?’

‘Not yet.’

‘Get her on the phone now. Just tell her that you're driving back.’

“He was just trying to keep me accountable in that way, too.”

Thunderbolts catcher Kyle Harbison, 24, still laughs thinking about the first time he met Jenks.

Harbison had played with Tayden Hall — Toby Hall’s son — at State College of Florida. In search of a shot at pro ball, he reached out to Hall to see if Windy City had a spot. Jenks was all for it.

“[Jenks] comes up to my locker, shakes my hand, introduces himself, and all he says is, ‘Hey, I heard you were pretty good. Better not suck,’” Harbison said.

“I owe my professional career to that man.”

Independent ball isn’t glamorous. The pay’s low. The grind is constant. For most players, it’s a last shot at staying in the game.

But that’s not how Jenks treated it.

“You leave it out there every single pitch,” Reynolds said of Jenks’ biggest advice. “You don’t know when your last pitch is going to be, so you have to give it everything you got.”

Jenks knew that feeling well.

His career ended abruptly after he was a victim of a “concurrent surgery,” a practice where one doctor performs two procedures simultaneously. The botched back operation left Jenks on his deathbed and abruptly ended his career after the 2011 season — his only year with the Red Sox.

In a raw, unfiltered Players’ Tribune essay, Jenks opened up about that hellish stretch: the pain, the pills, the addiction, the divorce. He nearly died.

But he came back.

Jenks met his second wife, Eleni, in an Arizona rehab facility. He found his way back into the game to influence the next generation.

That’s what made Jenks such a magnetic presence in the clubhouse. He knew what it felt like to dominate on the biggest stage — and to lose everything that came with it.

He was the first one at the park, the last to leave. He handled everything from lineup cards to travel bookings.

“I was just surprised and shocked at how good of a manager he was,” Hall said, adding that Jenks had a future as a big league skipper. “Everybody thinks catchers or infielders make the best managers — not closing pitchers.

“He opened my eyes to how great he actually was at it, and to the relationship he had with the players.”

That leadership came in all forms — usually with a competitive edge.

He took pride in beating everyone at ping pong in the clubhouse. Golf outings got frustrating fast: Jenks smoked the field.

“We’re like, ‘How’d you get so good?’” Reynolds said.

“And he goes, ‘Dude, I was in the big leagues. I had a routine. I did baseball every day. So when I was done, what do you think I did every day? Learn how to golf.’”

Last season, Kuzemka and Hall faced off in a friendly, best-of-five challenge.

“He had to strike me out three times for him to win,” Kuzemka said. “I had to get three hits.”

“Oh yeah, I caught that bet,” Harbison said. “Unhittable. Just unhittable.”

The velocity wasn’t the same, but the heat was still there. And a few curveballs buckled Kuzemka.

It’s that player-first mentality Hall hopes to carry on. He can’t replace Jenks — no one could — but the friendship that began back when Hall joined the White Sox in 2007 hasn’t gone anywhere.

In the days after Jenks’ passing, Hall left the Thunderbolts to fly back to Chicago, coordinate picking up Jenks’ family and spend the weekend celebrating the life of his best friend.

That’s when it hit him.