Fruit baskets to fruitfulness: How Raúl Ibañez became an MLB All-Star after every team passed on him – twice

“The most flagrant example I saw of teams missing out on a guy."

Nearly two decades. More than 300 home runs. An All-Star game appearance. Postseason heroics in pinstripes.

It’s hard to fathom how close Raúl Ibañez came to never achieving any of it.

One of the steadiest left-handed hitters of his generation, Ibañez found himself clinging to a roster spot a week after turning 30 — dead weight on a last-place team, unsure if his major league career was already over.

“That was rock bottom for me,” Ibañez admitted to Sports Illustrated in a 2012 interview.

After signing with the Kansas City Royals for the 2001 season, Ibañez was primed for the opportunity he never had with the Seattle Mariners: consistent playing time.

Instead, on June 8, he was designated for assignment (DFA’d) for the second time in five weeks — cast aside as a .150 hitter with shaky defense, subpar speed and no track record of big-league success — expendable to a team barreling toward 97 losses.

Twice, the Royals were willing to lose him for nothing.

Twice, every other team in baseball passed.

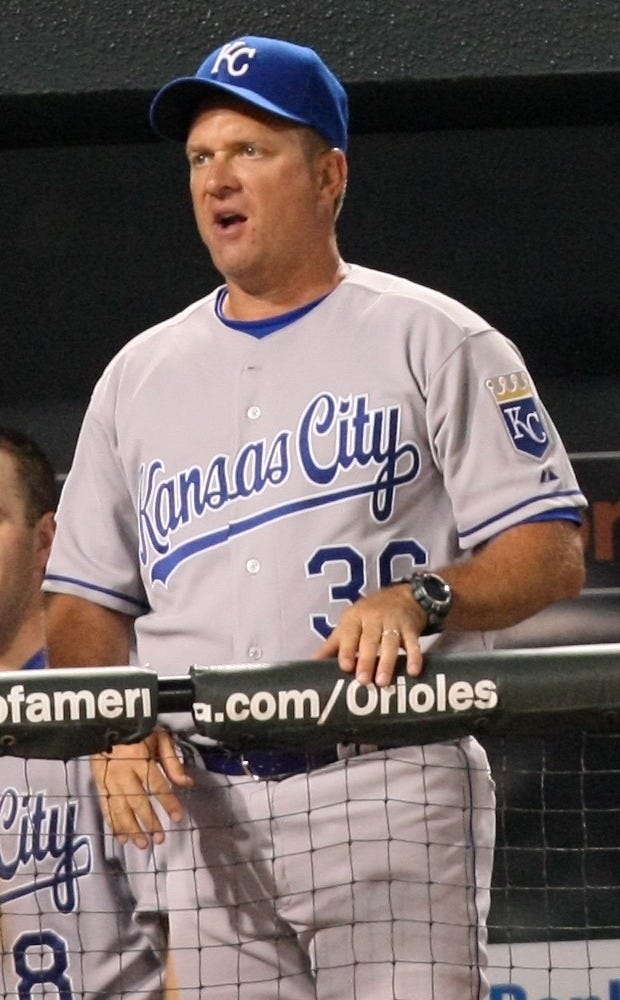

To then-Royals coach Tom Gamboa, none of that mattered – he saw something else.

“The most flagrant example I saw of teams missing out on a guy,” said Gamboa, a six-decade veteran of professional baseball, in an exclusive interview.

“Scouting is so sophisticated these days, and you can’t go to a big league game where there aren’t scouts from other teams behind the stands because everybody is looking to steal somebody. Or find their 41st-best player on the 40-man roster. Yet here, a guy went totally unnoticed.”

DREAMLESS IN SEATTLE

Years before two DFAs put his career in jeopardy, Ibañez found himself stuck in a different kind of limbo — assembling fruit baskets for Carnival Cruise Lines.

When Ibañez’s father, Juan Armando — a former chemist in Cuba — emigrated to the United States in the 1960s, he took a job as a warehouseman for the cruise company. Ibañez watched his dad work tirelessly, never taking a day off. It instilled in him a relentless work ethic.

At Miami Sunset Senior High School, Ibañez took every opportunity to hit — even if it meant pulling over on the side of the road after practice to take hacks into a fence, using orange traffic cones as makeshift tees.

“My buddies knew I wasn’t going to a party until I got my swings in,” Ibañez said. “That was just a discipline of doing what’s necessary to attain your goal.”

Yet, it was the job his dad got him on a cruise ship that he credits with his success.

“I jokingly [half-jokingly] say all the time that I got to the major leagues because of that job,” Ibañez told mental performance coach Brian Cain. “Because I’d sit there for four or five hours in a row and we’d go dead silent, my brother and I, and just do this monotonous, tedious job.

“And my only escape from it was visualizing myself in different major league ballparks, visualizing myself on different college fields, visualizing myself getting hits off the best pitchers in the district in high school.”

It worked.

Ibañez was selected by the Seattle Mariners in the 36th round — 1,006th overall — in the 1992 MLB Draft, a round that no longer exists.

And then he hit. And hit. And kept hitting, climbing the ladder through every level of the minor leagues, earning minor league player of the year honors in 1995.

He was on an “express train” to the majors –but there were roadblocks.

“He was a catcher and, to be honest, out of position,” said longtime Mariners coach and former manager John McLaren in an exclusive interview. “He worked hard but he wasn’t suited to be a catcher.”

A natural at the plate, but struggling defensively behind it, the Mariners shifted Ibañez to left field, where he would have a better chance for an MLB opportunity.

“I haven’t played the outfield in more than four years, so I know that there’s a lot I’ll need to work on,” he said to The Olympian. “But it’s flattering they think that much of me."

Ibañez was also buried on the depth chart, fighting for at-bats on an elite team behind a star-studded cast of Ken Griffey Jr., Alex Rodriguez, Jay Buhner, and Edgar Martínez.

He never appeared in more than 92 games in a season for Seattle, frequently shuttling between Triple-A Tacoma and the majors. Despite flashes of brilliance — including the first grand slam in Safeco Field history — his strong minor league production didn’t translate into sustained MLB success.

“He had a little bit of a long swing,” said McLaren. “…It looked like at times he was going to be a 4A player at best.”

The financially-challenged Royals could not pay to keep their best players, so the team sought cost-efficient diamonds in the rough. A free agent after the 2000 season, Ibañez was exactly the type of player Kansas City desired.

“This guy is going to hit,” then-Royals general manager Allard Baird asserted.

A month into the campaign, he didn’t hit much — at one point, going more than a week without an at-bat.

In early May, with Carlos Beltrán injured, the Royals DFA’d Ibañez to make room for 35-year-old journeyman Trenidad Hubbard, who replaced him in center field after a brief and shaky stint at the position.

“He was doing a good job for us in Kansas City, but for some reason, people didn’t think he could hit left-handers,” Gamboa said. “It was just easier to platoon him to play somebody else when a left-hander pitched. I thought for sure somebody would claim him and they didn’t.”

Ibañez cleared waivers and reported to Triple-A Omaha before returning a few weeks later. Two feckless weeks later, Ibañez was DFA’d again, this time as the corresponding move to clear a 40-man roster spot for infielder Carlos Febles, who was coming off the injured list.

“He’s a quality human being, up front with you all the time and he’s a hard worker,” then-Royals manager Tony Muser said of Ibañez, adding that the team would do “everything possible” to find a better opportunity for him elsewhere.

Again, no trade or waiver claim materialized, and Ibañez was sent to Triple-A. But not before he made a career-changing pitstop.

“It turned out to be the best thing that ever happened to me,” Ibañez said.

SEITZ’ SET ON SUCCESS

During his struggles with the Mariners, Baseball Prospectus pulled no punches in assessing Ibañez’s skillset entering 2000.

"Unless he becomes more selective at the plate and hits for more power, he won't be in the majors long enough to draw a full pension."

So before he reported to the minors, Ibañez made a detour: a visit to former Royals All-Star third baseman Kevin Seitzer, who was giving hitting lessons in Overland Park, Kansas.

By then, Ibañez understood the reality: a 30-year-old, twice-DFA’d, bat-first player with no history of consistent major league production doesn’t get many more chances.

If there was a fix, a tweak, a shift, a breakthrough — he wanted to find it.

Seitzer didn’t need long to spot something.

“The player that I saw then was very strong with extremely quick hands, talent oozing out of him,” Seitzer, the current Mariners hitting coach, told SI in 2012. “But he was so tight at the plate and he yanked everything. He had no concept whatsoever of taking a fastball and hitting it the other way.”

That fix changed everything for Ibañez; his approach was tailored for success at the game’s highest level. The results were nearly instantaneous once he returned to the majors less than two weeks later as the corresponding move for outfielder Dee Brown hitting the injured list.

In 80 games the rest of the season, Ibañez raked: .301 batting average with 13 home runs and 51 runs batted in (RBIs).

“Kevin taught me how to hit,” Ibañez said. “My whole life, I had just hit, but I didn’t know how to hit. He gave me a solid foundation. He taught me how to be fluid with my hands, how to hit with my legs, and most important, to be stubborn with my approach, trying to hit to left-center.”

With soon-to-be expensive stars Johnny Damon, Jermaine Dye and others traded, Ibañez firmly cemented himself as a stalwart in the Royals lineup for two additional seasons.

In 2002, Ibañez slashed a robust .294/.345/.454 with 24 homers and 103 RBIs. The next year, he swatted another 18 roundtrippers with 90 RBIs. The potential was replaced with results.

“Fortunately for Kansas City, when he came back the next time, Tony Pena was the manager and he played [Raúl] against lefties and righties and was batting fifth behind [Carlos] Beltran and Mike Sweeney and next thing you know, he’s hitting 30 home runs and driving in 100 [runs],” Gamboa said.

“With a lot of players, when you go to the park not having to look at the lineup to see if you’re in there, even if you’ve gone 0-for-4 two days in a row, the managers and coaches have even confidence [in you] to know you’re in the lineup, it takes a lot of the pressure off. That’s when your true ability comes up.”

RAUL THE ROOST

Outside of a brief rehab assignment in 2009 with the Lehigh Valley Iron Pigs, Ibañez never saw the minor leagues again.

He left the Royals to rejoin the Mariners in 2004 and enjoyed five standout seasons, including setting a then-career-high with 33 home runs and 123 RBIs in 2006.

McLaren, who returned to the Mariners in 2006 as coach and later assumed managerial duties in 2007, had the unique vantage point of seeing Ibañez evolve from a positionless career minor leaguer in the making to a potent middle-of-the-order weapon.

“I kind of use him as an example of somebody that had to fail before they succeeded,” McLaren said.

“I saw him come from a Class-A ball player in Seattle, come to spring training with us as an extra catcher, start playing games with us, eventually working his way back to the big leagues, position change, struggling, not playing every day, getting sent back to the minor leagues. I saw it unfold in front of me, and then when I came back [as manager], he's an established major league player. He's right there at he star level.”

Also, while never an elite defender – prone to some questionable throws – Ibañez developed into a serviceable outfielder. In 2004, he ranked fourth among all left fielders in Ultimate Zone Rating (UZR), a metric that estimates how many runs a player saved or cost his team on defense compared to an average fielder at the same position.

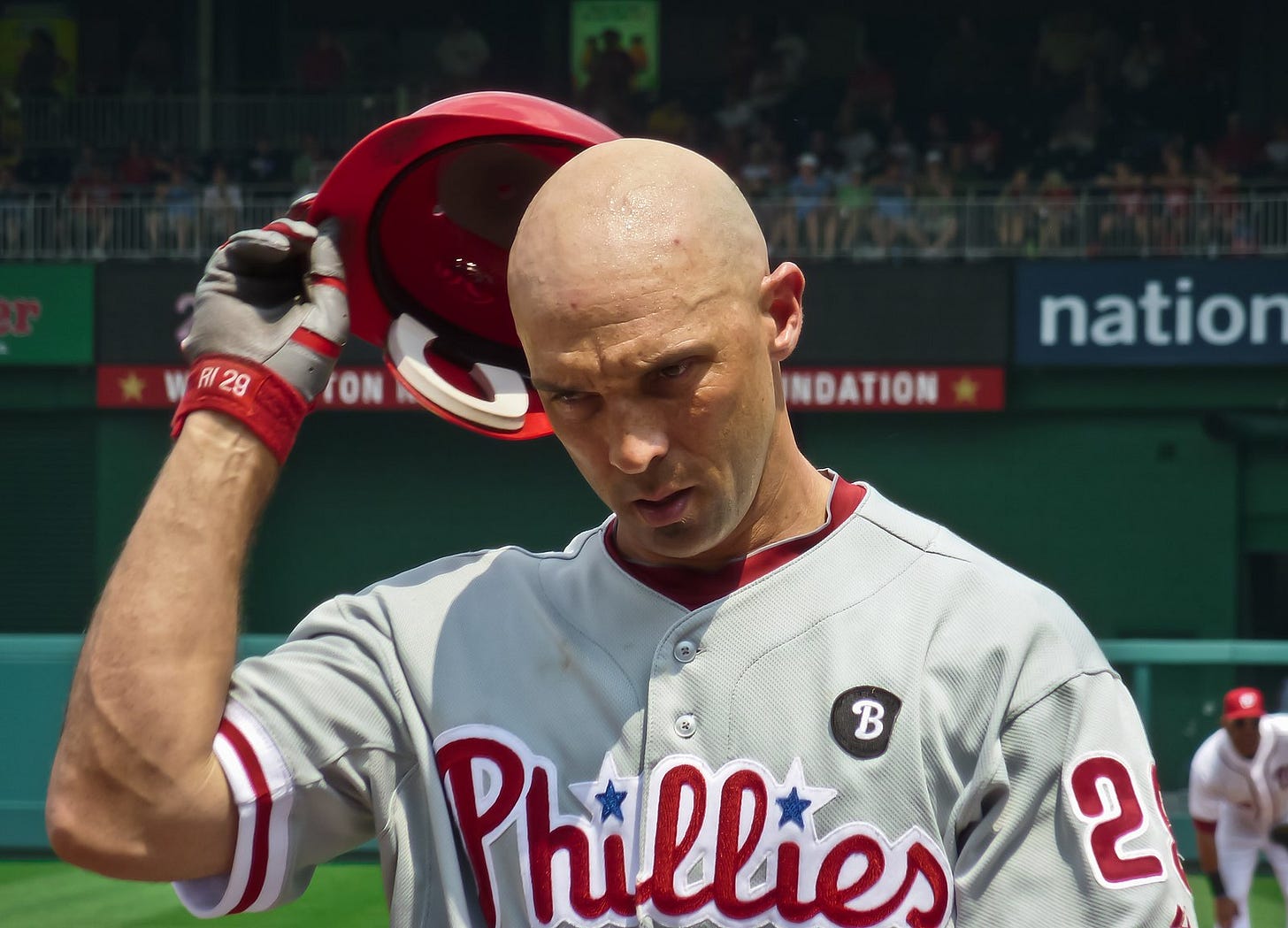

Ibañez left the Mariners after 2008 to sign a lucrative three-year, $31.5 million contract with the Philadelphia Phillies. He promptly set a new career-high in homers (34) at age 37. The on-field excellence was rewarded with an All-Star game appearance.

"You know, I asked Edgar Martinez once, 'Why does everybody talk about age 35 like I'm going to die?'" Ibañez told ESPN about his late career success. "And he told me he thought [his] prime was from 36 to 39. He said that was when he felt like his knowledge, combined with his physical skills, enabled him to replicate his swing and figure stuff out in the batter's box. And that's when he felt was his best time. He told me that decline at 35 was 'for people who don't work as hard as us.'"

It came full circle: Ibañez, once buried behind stars in Seattle, had become the battle-tested veteran — like Edgar Martínez and Jamie Moyer — who struggled early but thrived with age.

“I would think he would give a lot of credit to those veteran players, and he broke in with talking to him,” McLaren said of his early Mariners stint. “Everybody liked him. I mean, my goodness, how could you not like this guy? He didn't have a big ego, he wasn't boisterous, he didn't try to be a big loud voice. He did his work and he worked hard.”

Ibañez played until he was 42. He didn’t maintain the same offensive pace, but the final chapters of his career were some of his best.

In 2012, Ibañez provided several big hits for the New York Yankees – none bigger than his dramatic playoff exploits.

With the Yankees trailing 2-1 in Game 3 of the 2012 American League Division Series, Ibañez came off the bench to hit for the struggling Alex Rodriguez – his former Seattle teammate – in the ninth inning and sent Yankee Stadium into a frenzy with a game-tying homer.

Three innings later, Ibañez walked it off with another home run.

"Unbelievable," Rodriguez said after the game. "It was just one of the best performances I've ever seen."

In 2013, he returned to Seattle – again – and popped 29 bombs, tying Ted Williams for the most home runs hit in a single season by a player 40 or older.

After retiring, Ibañez seamlessly transitioned into front office and broadcast work, emerging as a respected voice in player development. Today, as the Dodgers' vice president of baseball development and special projects, he mentors the next generation.

“Raúl is invaluable,” Dodgers hitting coach Robert Van Scoyoc told The Athletic. “You can’t explain how much he helps.”

In 19 seasons, Ibañez became the ultimate bridge — from fringe prospect to All-Star, from waiver-wire warrior to playoff legend.

Perhaps one day he will manage a major league team, able to relate with everyone from the last man on the roster to the superstar batting third. But if his career has proven anything, he will leave no stone unturned in search of success.

“I really think there’s not a job in baseball Raúl couldn’t do,” McLaren said. “This is going to be a stretch, but I mean, I’ll put commissioner in that role too.”

SOURCES

Chen, A. (2012, October 16). Albert Chen: Ibañez authoring fascinating twist in remarkable career story - Sports Illustrated. SI. https://www.si.com/more-sports/2012/10/16/raul-ibanez-yankees-playoffs

Mpm, B. C. (2021, May 27). PODCAST: The mental game of a 19-Year MLB player Raúl Ibañez | - Brian Cain Peak performance. Brian Cain Peak Performance. https://briancain.com/blog/raul-ibanez-podcast.html

Carig, M. C. (2012, April 15). Raul Ibanez’s work ethic fueled his success and he hopes it continues. Star-Ledger. https://www.nj.com/yankees/2012/04/raul_ibanezs_work_ethic_fueled.html

Fowler, C. F. (2014, April 17). Angels’ Raul Ibanez still going strong at age 41. Los Angeles Daily News. https://www.dailynews.com/2014/04/17/angels-raul-ibanez-still-going-strong-at-age-41/

Waiting for their big day. (1996, June 23). The Olympian.

Posnanski, J. (2014, July 1). The remarkable career of Raul Ibanez - NBC Sports. NBC Sports. https://www.nbcsports.com/mlb/news/the-remarkable-career-of-raul-ibanez

Kaegel, D. K. (2001, May 5). Hubbard starts in center. The Kansas City Star.

Kaegel, D. K. (2001b, June 9). Febles returns to lineup. The Kansas City Star.

Uhlman, H. U. (n.d.). Ibanez brings treasure trove of experience to Dodgers staff | Think Blue LA. https://thinkbluela.com/2016/02/ibanez-brings-treasure-trove-of-experience-to-dodgers-staff/

Stark, J. (2009, June 16). Does life begin at 37 for Philadelphia Phillies left fielder Raul Ibanez? - ESPN. ESPN.com. https://www.espn.com/mlb/columns/story?columnist=stark_jayson&id=4262125

Begley, I. (2012, October 10). 2012 ALDS -- Alex Rodriguez batting third in New York Yankees’ Game 3 lineup against Baltimore Orioles - ESPN. ESPN.com. https://www.espn.com/new-york/mlb/story/_/id/8487161/2012-alds-alex-rodriguez-batting-third-new-york-yankees-game-3-lineup-baltimore-orioles

Dutton, B. K. (2014, January 30). Quiet work earns Ibañez the Hutch. The News Tribune.

Rosenthal, K., & Ardaya, F. (2025, May 8). Andy Pages embraces his ‘superpower’ thanks to mentors like Raúl Ibañez. The Athletic. https://www.nytimes.com/athletic/6340881/2025/05/08/dodgers-andy-pages-raul-ibanez/

Tom Gamboa, interview with author, July 31, 2024

John McLaren, interview with author, May 29, 2025